Discovery Could Make Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Safer

PR Newswire

CINCINNATI, Feb. 20, 2026

Experts at Cincinnati Children's report proof-of-concept results that may sharply reduce the risk of a lethal side effect that has negatively impacted the use of revolutionary cancer immunotherapies

CINCINNATI, Feb. 20, 2026 /PRNewswire/ -- For many people diagnosed with cancer, treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has dramatically extended lives. Some of these treatments, such as Keytruda and Opdivo, have become familiar brand names.

However, for some patients, ICI cancer treatment also can prompt the immune system to attack heart tissue—a potentially lethal side effect.

Now, scientists at Cincinnati Children's report discovering a way to dramatically reduce that risk. Details were published Feb 20, 2026, in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

"This study makes a very important discovery that shows how to uncouple anti-tumor efficacy from cardiac toxicity. These findings have major implications for treating or avoiding immune related adverse events in cancer patients receiving immune check point blockade," says Chandrashekhar Pasare, DVM, PhD, director, Division of Immunology at Cincinnati Children's.

Pasare served as co-corresponding author on the study, along with Jeffery Molkentin, PhD, director of the Division of Molecular Cardiovascular Biology. First author Kathrynne Warrick, an MD-PhD student, led the research work.

What are ICIs?

Immune checkpoint inhibitors work by cutting off signals from "checkpoint" proteins that cancer cells use to hide from the immune system. This allows the body's T cells to recognize and destroy tumor cells.

Since 2011, when the first drug (Yervoy) was approved in the U.S. for treating metastatic melanoma, this form of treatment has revolutionized outcomes for many types of cancer. In fact, the inventors – James Allison and Tasuku Honjo – received the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2018 for their discovery.

However, in about 2% of all cancer patients receiving ICIs, the treatments can cause myocarditis—an inflammation of heart muscle. About half of these patients die from this complication, even if they survive their cancer.

Promising path to prevention

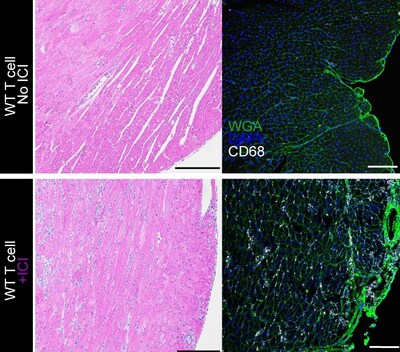

To better understand the complication, the research team engineered a new mouse model that accurately mimics immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced myocarditis. Then, in a series of advanced experiments, the team pinpointed a key driver of the complication: CD8 T cell–derived tumor necrosis factor (TNF).

Importantly, the team found that this complication from checkpoint inhibitors is not caused by tumors exhausting the body's cancer-specific T cells, but rather through causing new production of "autoreactive" T cells that see healthy cardiac muscle cells as targets in addition to cancer cells.

The team went on to show, in mice, that blocking TNF signaling specifically through the TNFR2 gene product prevented the inflammatory cycle from starting in the heart.

"Checkpoint inhibitors allow TNF signaling to trigger CD8 T-cells that are specific to antigens on cardiac myocytes, which in turn leads to life-threatening arrythmias," Molkentin says. "We used a targeted TNF blockade method to prevent this cycle in our mouse models. If these results can be replicated in humans, TNF blockade should prevent cardiac toxicity without compromising the anti-tumor benefits of ICIs."

Next steps

More research is needed to determine if a narrowly focused TNF inhibitor would be safe for human use, and how long a patient might need to take such a drug. TNFR2-specific antibodies remain in development stages. The team also wants to determine whether similar approaches can also prevent immune-related adverse events affecting other organs.

About the Study

Cincinnati Children's co-authors also included Anne Katrine Johansen, PhD, Mengchi Jiao, PhD, Megan Linnemann, BS, Irene Saha, PhD, Suh-Chin Lin, PhD, Charles Vallez, BS, and Thomas Hagan, PhD. These core services also contributed to the study: the Veterinary Services Facility, Research Flow Cytometry Core, Transgenic Animal and Genome Editing Facility, Integrated Pathology Research Facility, and the Bio-Imaging and Analysis Facility.

Funding sources included grants from the National Institutes of Health (7R01AI123176, 5R01HL160765, and 5R01HL156852) and the American Heart Association.

![]() View original content to download multimedia:https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/discovery-could-make-immune-checkpoint-inhibitors-safer-302693662.html

View original content to download multimedia:https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/discovery-could-make-immune-checkpoint-inhibitors-safer-302693662.html

SOURCE Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center